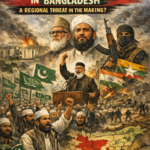

Bangladesh at the Brink: When Silence Enables the Persecution of Minorities and the State Flirts with Radicalism

Bangladesh is in the midst of a moral and constitutional emergency, and the most culpable actors are not only the street-level perpetrators, but the men and women in power who have decided—through silence, delay, and equivocation—that minority lives are an acceptable casualty of political transition.

Since the collapse of the last political order in August 2024 and the installation of an interim, non-elected administration, a disturbing and familiar pattern has re-emerged. Hindu homes and businesses have been vandalised, temples attacked, Christian communities terrorised, families displaced, properties confiscated, and individuals reportedly beaten or burned to death. The message being delivered through violence is chillingly clear: minority citizenship in Bangladesh is conditional, revocable, and negotiable.

This is not a law-and-order aberration. It is a systemic failure of governance, aggravated by political opportunism and moral cowardice. When a state cannot—or will not—protect its most vulnerable citizens, it forfeits its claim to being a republic. What remains is a hollowed-out structure where power exists, but justice does not.

The pattern is structural, not incidental

The recurring defence offered by authorities and political actors—that such violence is “political” rather than “communal”—is both disingenuous and dangerous. When the overwhelming majority of victims belong to religious minorities, when their homes, temples, and churches are disproportionately targeted, and when attacks spike precisely during moments of political rupture, motive cannot be divorced from identity. Political hostility becomes the camouflage under which communal violence operates.

Transitional moments in Bangladesh have historically exposed minorities to collective punishment. Each shift in power emboldens mobs who see minorities as politically defenceless, administratively unprotected, and socially expendable. The failure of the state to impose swift consequences reinforces this logic and converts sporadic violence into a repeatable strategy.

The interim government’s responses—statements of concern, promises of investigation, calls for calm—have followed a predictable script. What has been missing is urgency, transparency, and deterrence. Neutrality, in a transitional context, is not declared; it is demonstrated. And neutrality collapses the moment protection becomes selective or delayed.

Political parties and the calculus of silence

If the interim administration bears responsibility for enforcement, political parties bear responsibility for enabling the climate in which persecution thrives. Some instrumentalise minority suffering to score partisan points. Others remain conspicuously silent, fearing backlash from street power, radical networks, or majoritarian sentiment. In both cases, minorities are reduced to bargaining chips.

This strategic blindness is not accidental. Parties understand that radical groups possess mobilising power, particularly in periods of uncertainty preceding elections. Condemning violence without qualifiers risks alienating those forces. The result is a politics of omission, where silence functions as tacit approval and moral abdication is repackaged as pragmatism.

When leaders fail to draw red lines around minority protection, extremism does not need to win elections—it only needs to intimidate society into compliance.

The Pakistan comparison is a warning, not rhetoric

The growing comparison between Bangladesh and Pakistan is not made lightly, nor is it rhetorical exaggeration. It is a warning rooted in trajectory. Pakistan’s history of minority persecution did not emerge overnight; it evolved through the normalisation of mob violence, selective law enforcement, religious majoritarianism, and political appeasement of extremists.

Bangladesh does not need blasphemy laws or formal theocratic structures to replicate Pakistan’s lived outcomes. All it requires is what is already visible:

-

Weak or selective enforcement of law

-

Political incentives to appease hardliners

-

Social media–fuelled mob mobilisation

-

Bureaucratic indifference and delayed justice

This is how states emulate failure—incrementally, quietly, and without formal declarations.

Why radicalism is finding fertile ground

The slide toward radicalisation in Bangladesh is not about Islam as a faith. Bangladesh’s history is deeply rooted in linguistic nationalism, cultural pluralism, and coexistence. The threat comes from radicalism as a political tool—a mechanism to control streets, silence dissent, seize property, and reshape society through fear.

Several drivers are now clearly visible:

Impunity: When attackers face no meaningful consequences, violence becomes rational and repeatable—particularly for land grabs and economic dispossession masquerading as ideological outrage.

Transitional fragility: Political ruptures weaken policing and create contested authority, providing space for mobs to operate with confidence.

Instrumentalised identity: Minorities are framed as politically suspect or expendable, legitimising collective punishment.

Electoral opportunism: Aspiring power brokers calculate that signalling to radicals delivers street leverage and suppresses opposition.

Together, these dynamics do not merely threaten minorities—they corrode the state itself.

An appeal—and an indictment

To the interim government: legitimacy is not inherited by appointment; it is earned through protection. Stop governing through statements and start governing through action. Publish verified incident data regularly. Fast-track prosecutions. Suspend and prosecute officials who fail to act. Compensate victims transparently. Provide visible, proactive security to temples, churches, and minority neighbourhoods—before violence erupts, not after funerals.

To political parties: silence is not neutrality; it is complicity. If you seek power, demonstrate moral authority. Condemn attacks without caveats. Expel members implicated in violence and land grabs. Commit publicly and unequivocally to minority protection as a foundational principle of governance.

To the radicals and their enablers: you are not defenders of faith or nation. You are saboteurs of Bangladesh’s social contract. Burning homes, terrorising families, and attacking places of worship are not acts of devotion—they are crimes. And they are dragging Bangladesh toward a future defined by fear, isolation, and decline.

Bangladesh now stands before a stark choice: a republic that protects all its citizens, or a state that teaches minorities to fear their own homeland. History will remember which path was taken—and it will not absolve those who watched the fire and called it politics.

Bibliography / References

-

Reuters – Coverage on post-August 2024 communal attacks on Hindu homes and temples and minority displacement

-

Associated Press (AP) – Reporting on minority rights groups’ allegations against Bangladesh’s interim government

-

Amnesty International – Bangladesh country reports on minority protection and communal violence

-

UK Home Office – Country Policy and Information Notes (CPIN) on religious minorities in Bangladesh

-

The Daily Star (Bangladesh) – Reports on attacks on Hindu and Christian communities and public protests

-

Al Jazeera – Coverage of post-transition violence and minority fears in Bangladesh

-

International Crisis Group – Analysis of Bangladesh’s post-Hasina political transition and risks of communal violence

-

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) – Comparative reporting on minority persecution in Pakistan