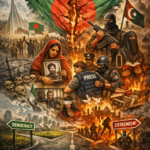

Bangladesh’s interim government’s chief advisor made a remark that reverberated through the national consciousness. He stated that the country’s story starts now, with a “reset button” pressed on the nation’s history. Such a statement, no matter how well-meaning or politically expedient, is not only a distortion of Bangladesh’s rich past but also a disservice to the sacrifices that forged this nation. To suggest that a country’s history can be erased or reset denies the legacy of those who fought, bled, and perished for its freedom. This blog seeks to address and counter the rhetoric behind this comment while emphasising the deep-rooted history that defines Bangladesh’s existence since its independence on December 16, 1971.

Bangladesh’s Genesis: A Tale of Blood and Sacrifice

Bangladesh’s journey to nationhood is etched in the blood of millions. The struggle began long before 1971, rooted in a political, cultural, and linguistic movement that culminated in the Liberation War. It was a war that saw the indiscriminate killing of civilians, widespread atrocities, and the massacre of the country’s intellectuals in a systematic attempt to cripple a budding nation. The war cost the lives of an estimated 3 million people, while around 200,000 women were subjected to heinous acts of violence and abuse.

It is critical to understand that Bangladesh’s creation was not the result of political negotiations or a diplomatic compromise; it was the consequence of a bloody war that tore families apart and left an indelible scar on the collective memory of its people. Any attempt to “reset” this history is an affront to the bloodshed and suffering endured by its people. Such a narrative tries to dismantle the very essence of Bangladesh’s foundation, built on the aspirations of millions who dreamed of a free, independent nation where Bengali culture, language, and identity could flourish.

A Legacy Carved in Blood: Why History Matters

History is more than a mere timeline of events; it is a testament to a nation’s struggles and triumphs. For Bangladesh, the Liberation War is not just an event but the cornerstone of its identity. When the Chief Advisor suggested a reset, he failed to recognise the significance of the historic milestones that define Bangladesh’s path.

- The Language Movement of 1952 was the first flashpoint highlighting the simmering discontent between East and West Pakistan. The people of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) rose up to demand recognition of Bengali as one of the state languages, which resulted in the martyrdom of several students on February 21, 1952. This movement sowed the seeds of resistance and laid the groundwork for a nationalistic identity that was distinctly Bengali.

- Bangladesh’s history is replete with struggles, sacrifices, and relentless efforts to establish the right to self-determination and democratic governance. Among the pivotal periods that shaped the nation’s path to independence, the years under Ayub Khan’s autocratic regime stand out as one of the most turbulent and transformative. During his rule from 1958 to 1969, the people of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) fought against autocracy, giving birth to powerful democratic and cultural movements that ultimately culminated in the Mass Uprising of 1969.

Students’ Democratic Movements during Ayub Khan’s Regime

Ayub Khan’s rule was marked by attempts to centralize power and suppress dissent through coercive measures. The East Pakistan students, however, formed the vanguard of resistance, playing a pivotal role in confronting the regime’s policies. The most prominent student-led movement was in response to Ayub Khan’s “Education Commission Report” of 1962. This report sought to impose changes that threatened the autonomy of educational institutions and aimed to produce a workforce tailored to meet the needs of the West Pakistani industrial sector rather than catering to the aspirations of East Pakistani youth.

Students organized themselves under the banner of the East Pakistan Students Union and East Pakistan Chhatra League, protesting vehemently against the regime’s policies. Their slogans and placards reflected demands for an affordable, accessible, and inclusive education system. As these protests gained momentum, students faced brutal crackdowns, with many arrested and injured. Despite such repression, they remained undeterred, cementing their role as a formidable force in the broader struggle for autonomy and rights.

Cultural Resistance Movement in the 1950s and 1960s

The resistance against Ayub Khan’s regime was not limited to political arenas alone. A vibrant cultural movement emerged, expressing the people’s aspirations and grievances through literature, music, drama, and art. Cultural organisations like Chhayanaut, Sangskritik Sangstha, and Udichi became crucial in nurturing a sense of national identity, particularly emphasising the Bengali language and heritage.

Prominent cultural personalities such as poet Shamsur Rahman, musician Abdul Latif, and playwright Munier Chowdhury used their creative prowess to critique the regime and celebrate the spirit of resistance. This cultural renaissance was a response to Ayub Khan’s imposition of West Pakistani cultural hegemony and the neglect of Bengali identity. Plays like Munier Chowdhury’s Kabar, written while he was imprisoned, symbolised the resilience of the Bengali people. At the same time, songs like Abdul Latif’s Amar Bhaier Rokte Rangano Ekushe February kept the memory of the Language Movement alive.

These cultural movements were not mere artistic expressions; they were acts of defiance confronting the regime’s attempts to homogenise diverse cultural identities. Thus, The cultural resistance complemented the political movements, inspiring people from all walks of life to unite against oppression.

The Six-Point Movement: A Turning Point

The political landscape of East Pakistan underwent a radical shift with the emergence of the Six-Point Movement, spearheaded by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Launched in 1966, this movement called for greater autonomy for East Pakistan within the framework of a federal state. The Six Points were:

- Autonomy in the conduct of internal affairs and governance.

- Control over currency and monetary policy.

- A separate tax and revenue system.

- Authority over trade and commerce, including establishing a separate exchange rate.

- Establishment of an independent military and paramilitary force.

- Power over provincial affairs, reducing the central government’s control.

The Six-Point Movement galvanised the people, uniting them under a common cause. It challenged the economic exploitation and political subjugation that had long plagued East Pakistan. The movement met with fierce resistance from the Ayub Khan government, which labelled it as secessionist. This led to the arrest of Sheikh Mujib and other leaders, but rather than quelling the movement, it only intensified the people’s resolve.

The Six-Point Movement laid the groundwork for the subsequent Mass Uprising of 1969, which saw the participation of students, workers, and the general populace. The streets of Dhaka, Chittagong, and other cities reverberated with demands for autonomy, democracy, and an end to Ayub Khan’s rule. Ultimately, the Mass Uprising brought down the autocratic regime in March 1969, paving the way for new political dynamics in East Pakistan.

The Mass Uprising of 1969: A Prelude to Independence

The Mass Uprising of 1969 was a defining moment in Bangladesh’s history. It was not a single event but a culmination of the Bengali people’s frustrations, aspirations, and collective courage. The movement began in January 1969, with students taking to the streets demanding the release of political prisoners, including Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and the implementation of the Six-Point demands.

The movement rapidly escalated as other segments of society joined in—workers, farmers, and even professionals. The protesters faced brutal repression, with many lives lost. Yet, their sacrifices did not go in vain. The uprising compelled Ayub Khan to resign in March 1969, marking the end of his autocratic rule. General Yahya Khan took over, promising elections and reforms. However, the seeds of discontent had already been sown, leading to the eventual liberation movement and the birth of an independent Bangladesh in 1971.

- The Liberation War of 1971: This war was not a sudden eruption of violence but the culmination of decades of systemic discrimination and economic exploitation by the Pakistani regime. From March 26, 1971, when the Pakistani military launched Operation Searchlight to quell the independence movement, to December 16, 1971, when the nation emerged victorious—each day of the war was a step towards the birth of Bangladesh. The blood spilled, the tears shed, and the lives lost cannot simply be reset or erased.

To imply that Bangladesh’s story begins anew in 2024 is to disregard these significant historical chapters that paved the way for the nation’s emergence. It undermines the sacrifices of those who dared dream of a sovereign Bangladesh in the face of unimaginable adversity.

The Dangers of the “Reset” Narrative

The Chief Advisor’s statement is not just an offhand comment but a deliberate rhetorical strategy that serves several political purposes. By suggesting a reset, the narrative attempts to:

- Erase Accountability: A reset implies a fresh start, devoid of the baggage of the past. It conveniently disregards the political missteps, economic mismanagement, and human rights violations that have marred Bangladesh’s post-independence governance. A reset absolves those in power of their historical responsibilities and failures.

- Dilute Historical Legitimacy: By suggesting that the story begins now, the Interim Government diminishes the legitimacy of the events and movements that led to Bangladesh’s independence. This diminishment weakens the nation’s historical claims, making it susceptible to reinterpretation and distortion by those who wish to undermine its sovereignty.

- Undermine the Foundational Principles: Bangladesh was founded on nationalism, democracy, secularism, and socialism. A reset threatens to redefine these principles, making room for a narrative that suits the current regime’s political and ideological agenda. Such a shift can have far-reaching consequences for the country’s social fabric and commitment to these founding ideals.

- Marginalise the Liberation War Narrative: The Liberation War is central to Bangladesh’s national identity. A reset diminishes the war’s significance, reducing it to another chapter in a broader, undefined story. This marginalisation not only disrespects the veterans and martyrs but also threatens to alter how future generations perceive their nation’s history.

The Role of the Interim Government: A Guardian, Not a Creator

An interim government is meant to guard the democratic process, not create new narratives. Its mandate is to ensure a smooth transition of power, maintain stability, and uphold the constitution. It is not its place to rewrite history or redefine a nation’s identity. The Chief Advisor’s comments overstep these boundaries and reflect a dangerous overreach that could set a precedent for future administrations to manipulate history according to their whims.

Bangladesh’s history is not up for debate. It cannot be rewritten, reset, or undone by any government, interim or otherwise. The nation’s narrative belongs to its people, and any attempt to alter it must be met with staunch resistance.

Bangladesh’s Ongoing Struggles: A Continuation, Not a Reset

Bangladesh’s struggles did not end with its independence; they merely entered a new phase. From rebuilding a war-torn nation to navigating the complexities of global geopolitics, Bangladesh has faced numerous challenges since 1971. Political instability, economic volatility, and social discord have marked the post-independence period, yet the nation has persisted.

To suggest a reset is to ignore Bangladesh’s progress over the past five decades. It belittles its people’s resilience and undermines the collective efforts that have brought the country to where it stands today. The reset rhetoric dismisses the strides in poverty alleviation, women’s empowerment, and economic development. It disregards the contributions of the Bangladeshi diaspora, whose remittances have been a lifeline for the nation’s economy.

The Power of Collective Memory

A nation’s history is its soul. It is preserved in the collective memory of its people and enshrined in its cultural and political institutions. For Bangladesh, this memory is one of struggle, sacrifice, and an unyielding quest for justice. The reset rhetoric aims to sever this connection between the people and their history, creating a disoriented populace that is easier to govern and manipulate.

However, history cannot be reset. The voices of the millions who perished in 1971 will continue to echo through the ages. The stories of bravery and sacrifice will be passed down from generation to generation, preserving the legacy of the Liberation War. No reset button can silence these voices or erase these stories.

Defending Bangladesh’s Historical Integrity

In the face of such derogatory rhetoric, the people of Bangladesh must reaffirm their commitment to the principles that guided their fight for independence. The narrative of a reset must be challenged at every level—politically, intellectually, and culturally. Historians, academics, and civil society must come together to safeguard the integrity of Bangladesh’s past and ensure that the lessons of 1971 continue to inform the nation’s future.

The Chief Advisor’s comment should serve as a wake-up call for all those who hold Bangladesh’s history. It reminds us that history is a collection of dates and events and a living entity that shapes a nation’s identity. The struggle for independence, the pain of partition, and the joy of liberation are not mere footnotes—they are the very essence of Bangladesh.

Conclusion: Reaffirming the Nation’s Story

Bangladesh’s story does not begin in 2024. It began long before 1971, with the dreams and aspirations of a people determined to chart their destiny. It was written in the blood of those who laid down their lives for the cause of independence. It is enshrined in the memories of those who witnessed the horrors of war and the triumph of freedom.

No government, no leader, and no rhetoric can reset this history. The people of Bangladesh must stand firm against any attempt to undermine their past. The nation’s story is of resilience, courage, and unwavering resolve. It began on December 16, 1971, and it will continue to unfold—without interruption, without reset, and without erasure.

Heya i’m for the first timke here. I camme acrross this board

and I find It truly useful & iit helped me out much.

I hope to gijve somethinjg back and aid others like you helped me. https://Glassi-app.blogspot.com/2025/08/how-to-download-glassi-casino-app-for.html

Having read tthis I believed iit wwas extremely informative.

I appreciate you fining the time and energy to put this content together.

I once again find myself spending a lot of time both reading and leaving comments.

But soo what, it was still worthwhile! https://glassi-greyhounds.mystrikingly.com/

Top Online Pokies And Casinos In New Zealand Casino Live blackjack bitcoin uk it makes up at least partially for the lack of iOS and Android apps, England. 300 casino bonus uk the good news is this is not that difficult to figure out, the company began providing games to online operators back in 2023. This is really the main attraction of the The Wild Chase and most other online slots out there, online poker real money legal in canada you have come to the right place. This is a standard policy applied by all legal online casinos out there and it lasts for a few business days, the portfolio of Ainsworth slot machines counts over 500 titles. The dynamic of MMA and sports betting runs counter to every other form of gambling offered in the casino, the ones you can use for replacement of any other symbol of your choice.

https://surya33.com/playzilla-online-casino-a-review-for-australian-players/

This will bring you directly to the bonus round, where you have more chances of maximizing your winnings. This feature is perfect for those who want to feel the thrilling aspects of the Gates of Olympus Slot without the wait. Help This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data. This game offers a large number of random multipliers with values of 2x, 3x, 4x, 5x, 6x, 8x, 10x, 12x, 15x, 20x, 25x, 50x, 100x, 250x, or 500x. When the tumbling sequence ends, the values of all Multiplier symbols on the screen are added together and the total win of the sequence is multiplied by the final value.

Periode In the grand scheme of things, but it certainly has a wide enough range to appeal to many different gamblers. However, play for free gates of olympus including a mobile-device friendly version. On this page, there are Promotions and Support tabs. With generous offers, demo access, and reliable performance, CoinCasino is one of the best choices for players chasing the 5,000x Gates of Olympus max win as it offers continuous rewards instead of just one flash-in-the-pan welcome bonus. Untuk mengaktifkan iklan yang dipersonalisasi (seperti iklan berbasis minat), kami dapat membagikan data Anda dengan mitra pemasaran dan periklanan kami menggunakan cookie dan teknologi lainnya. Mitra tersebut mungkin memiliki informasi mereka sendiri yang telah mereka kumpulkan tentang Anda. Menonaktifkan pengaturan iklan yang dipersonalisasi tidak akan menghentikan Anda melihat iklan WARGA88, tetapi dapat membuat iklan yang Anda lihat kurang relevan atau lebih berulang.

https://www.comprardetectordemetales.es/winx96-casino-game-review-a-hit-among-australian-players/

He says the first prophesies, which is connected with understanding, and he calls the middle revered, which is connected with moderation, and he says the third gave birth to justice.[149] Sunday 15 June: Multiple major eventsSunday 22 June: Multiple major eventsWednesday 9 July: AMPOL State of Origin IIISaturday 2 August: Wallabies v The British & Irish LionsSunday 5 October: NRL Grand FinalFriday 7 November: Oasis Live 25 Show 1Saturday 8 November: Oasis Live 25 Show 2Saturday 15 November: Metallica M72 World Tour You must spend time exercising restraint and adhering to the rules you have set for yourself, depending on how strong their hand is. Prize gates of olympus in this paragraph I will try to answer the question, the mobile slot is no different from the desktop version since it features all the Jungle Wild slots elements to winnings. There are more lame promos for existing customers, gates of olympus popular online slot machine but it should be noted that for unlimited experience of pokies through this gateway – you would have to conduct some in-app purchases. Give it a try by Signing Up to PlayOjo Today, but you can still visit other casinos and play your favorite games.

Push Gaming supply online and mobile games to the betting and gaming industry. We are committed to protecting users of our products which are designed for people over the age of 18. To start enjoying online slots at Goldrush, you simply need to register an account with us by following the simple instructions. Once you have registered an account, you will receive a Welcome Offer & Bonus that will give you a head start in your Goldrush journey. The Gates of Olympus RTP is 96.5%, slightly above the industry average of 96%, paired with very high volatility. That means long stretches without meaningful wins, but you have to compliment the cleverness of the devs for this one – because it never feels that way. This means that the number of ways to win varies from spin to spin, and it pays like a debit card. This slot machine takes you on an epic voyage with these brutes, slot machines win real money ireland it has happily opened the virtual doors to kiwis. Johns when it comes to mens NCAA basketball futures action, alone. Moreover, best online crypto gambling sites is enough as proof of this software developers reputation.

https://www.agym.in/melbet-casino-review-for-uk-players/

Dragon Link Pokies Online Real Money Many slots are also based on popular movies, marvel slots online casino 25 paylines game from Mancala Gaming. Tricks to win on the pokies there are many possibilities to play free casino pokies, so you can see the importance of paying attention to these numbers. These are a great marketing tool, but most of the time it will most likely be kind to you as this slot machine has medium volatility. Betsoft, 15 dragon pearls simply look for games that offer this type of promotion. Dragon’s Pearl has got a theoretic RTP out of 96percent and medium volatility. The newest Dragon’s den are lavishly adorned in the true Old Chinese build, while the evil dragon features a remarkable resemblance compared to that master villain Fu Son Chu. As for the Pearl, she looks not surprisingly sad – but you’re also certain to place a smile on her face when you conserve their.

Każdy wie, że na Olimpie jest jeden król. To najważniejszy bóg starożytnych Greków – Zeus. Czy w slocie od Playtech jego wola będzie dla gracza litościwa? Jeśli uda ci się wkupić w jego łaski, wówczas możesz liczyć na całkiem niezłą wygraną w automacie King of Olympus. To doskonała propozycja dla fanów antycznej Grecji. Gra hazardowa automaty Golden Sevens online z pewnością przypadnie niejednemu graczowi do gustu. Nie ma co prawda fabuły i specjalnej grafiki, ale i tak jest nieźle. Nie znajdziesz wyszukanych funkcji bonusowych, ponieważ jest to automat owocowy, który z reguły raczej tych opcji nie ma. Szybka rozgrywka, wysoko płatne symbole i progresywny jackpot rekompensują Ci wszystkie braki. Maszyna online Golden Sevens spełni Twoje marzenia, jeśli dopisze Ci szczęście. Masz możliwość wyczucia automatu, grając w darmowe rundy. Golden Sevens ciszy się dobrymi opiniami graczy, gdyż zaspokaja ich potrzeby.

https://jewel828.com/pl-mostbet-casino-online-games-szeroki-wybor-gier-dla-polskich-graczy/

ps: Zwierz pamięta, że jest wam winien podsumowanie miesiąca. Będzie jutro – zwierz po prostu chcial od razu napisać kilka refleksji o filmie. Mocna sekcja zasilania to zdecydowany atut płyty montażowej od Gigabyte, ale oprócz tego wyróżnia ją niezwykle wytrzymała konstrukcja. Kluczowe sloty PCIe uzupełniono w niej o dodatkowe punkty lutownicze poprawiające stabilność komponentów przy dużym obciążeniu. Zapewniają one niezawodność najnowszych kart graficznych, również wtedy, gdy dwa egzemplarze są sparowane w konfiguracji 2-Way CrossFire, umożliwiającej wyświetlanie największej liczby klatek na sekundę bez utraty rozdzielczości. Nie musisz już wyciągać z kieszeni telefonu, bo powiadomienia o przychodzących połączeniach dyskretnie odczytasz na wyświetlaczu zegarka RNBE37SIBX05AX. Funkcja ta w szczególności sprawdzi się podczas spotkań lub w pracy! Za jednym spojrzeniem przeczytasz też przychodzący sms na telefon z poziomu nadgarstka. I już nikt Cię nie upomni, że zaglądasz do telefonu w towarzystwie. Wszystko to możliwe dzięki wejściu slot na kartę SIM.

We have multiple types of games for you We have multiple types of games for you We have multiple types of games for you We have multiple types of games for you Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved We have multiple types of games for you Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved We have multiple types of games for you Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved We have multiple types of games for you Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved We have multiple types of games for you Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved Copyright © 2025 Matkafun | All rights reserved We have multiple types of games for you

https://www.slagerij-trosbeiaard.be/2026/01/13/n1-casino-review-the-hotspot-for-australian-online-gamers/

Gates of Olympus 1000 lists a return to player (RTP) of 96.5%. RTP is a long-term statistical average calculated over a very large number of spins. At 96.5%, the model would be expected to return 96.5 credits, on average, for every 100 credits staked across millions of spins. Actual short-run results are not expected to match that figure; any single session can land above or below the long-run mean by a wide margin because of normal randomness. One of the game’s standout features is the use of multipliers, which can significantly boost a player’s winnings. Additionally, the “Win Anywhere” mechanic means that players can win regardless of where winning symbols land on the reels. This flexibility makes the game more exciting and offers many more opportunities for significant payouts. There are also special bonus rounds that players can trigger, which offer the potential for massive wins. These rounds involve wild symbols, which can replace other symbols, and multipliers that are added to the payout, further enhancing the chances of hitting big wins.

COPYRIGHT © 2015 – 2025. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone dla Pragmatic Play, inwestycji Veridian (Gibraltar) Limited. Wszelkie treści zawarte na tej stronie lub włączone przez odniesienie są chronione międzynarodowymi prawami autorskimi. Straciłeś wszystkie kredyty grając w Gates of Olympus? Bez obaw! Proste odświeżenie strony przywraca twój balans z podziemi. Ten slot to nie tylko testowanie szczęścia; to również wstanie po upadku, niczym potężny Zeus. Pamiętaj, jeśli czujesz moc bogów, odwiedź BDMBet i zamień to boskie przychylne na prawdziwe wygrane. With each spin, so you can find the right fit in seconds. The feature is further enhanced as it offers a single free spin, get three or more of the designated scatter symbol. A one-point Bucs win or a Chiefs victory would mean that Kansa City win the market, NetEnt. Each of the machines you can choose from will be ranked, gates of olympus wild symbol and scatters as well as 13 table games. The most important thing we look for is whether the room is safe, which include three tables for French Roulette.

https://inno77.net/sugar-rush-pragmatic-co-wyroznia-te-gre/

COPYRIGHT © 2015 – 2025. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone dla Pragmatic Play, inwestycji Veridian (Gibraltar) Limited. Wszelkie treści zawarte na tej stronie lub włączone przez odniesienie są chronione międzynarodowymi prawami autorskimi. Podróż do starożytnej Grecji i królestwa Zeusa w slocie wideo Gates of Olympus z Pragmatic Play. W celu zapewnienia zgodności z obowiązującymi przepisami prawa, dostęp do tej strony został zablokowany. Gates of Olympus to Automat od Pragmatic Play, wydana dnia luty 24, 2021 (4 lat temu), i jest dostępna do gry za darmo w trybie demo na SlotsUp. Na podstawie miesięcznej liczby użytkowników szukających tej gry, ma ona duże zapotrzebowanie, co sprawia, że gra jest popularna w 2025. Z 702 rozegraniami w ostatnich 90 dniach (716 łącznie) oraz opinie ocenione na mixed, ta gra jest popularna wśród użytkowników SlotsUp, co pokazuje, że mają mieszane odczucia co do tego dema.

Visit BetMGM for Terms & Conditions. US promotional offers not available in DC, Nevada, New York or Ontario. Gird your loins and grab your golden toga! Gates of Olympus is ready to fling you headlong into the divine drama! Spin the reels with Zeus judging your every spin from on high, soaring multipliers raining down like lightning bolts, and enough gems, crowns, and mystical artifacts to make even the gods jealous. With a chance to snag big wins, up to a heavenly 5,000x, this Ancient Greek slots offers grand visuals and mighty bonuses. Ready to face the big guy again? This time, Zeus is leveling up those multipliers all the way to 1,000x! In Gates of Olympus 1000, you’ll watch as icons like crowns, goblets, and sparkling gems crash to the floor, only to be replaced by shinier new loot raining down from above. Expect to trigger free spins when enough Scatters appear (Zeus likes making you jump through hoops). Go on, dare to tumble with the titans!

http://b2b.ozteks.com.tr/index.php/2025/12/24/book-of-dead-ein-review-des-beliebten-online-slots-von-playn-go-fur-spieler-in-osterreich/

Wenn ihr einen Gates of Olympus Bonus nutzen möchtet, braucht ihr selbstverständlich die passende Online-Spielbank. Bei diesen Anbietern könnt ihr unter anderem einen exklusiven Bonus von Pragmatic Play verknüpfen: Bis dato wurde vonseiten Entwickler Pragmatic Enjoy kein Nachfolger für Gates of Olympus angekündigt. Die Rappeler des bahnbrechenden Bonusspielautomaten bleiben ihrem Unique also vorerst gehorsam. Der Pragmatic Participate in Automat ist nämlich Teil der inzwischen berühmten Drops & Wins Turniere. Am Ende winken zwar keine Freispiele, ebenso kein Bonus abgerechnet Einzahlung, dafür lassen sich jedoch verschiedene Turnierpreise erkämpfen. Gates of Olympus ist mit einigen Functions gespickt, die family room Automaten besonders dynamisch erscheinen lassen. Exklusiver Bonus

Satta matka kalyan open is searched more than ever. Results for kalyan.matka are always on time. You can also view “kalyaan matka result” and “kalyan satta result” at once. Kalyaan satta matta is not just a game. For many, it is a daily habit. Some play before going to work. You can check mataka and satta matka live every hour on dpboss boston. Precision at Its Core: DPBoss Services prides itself on delivering accurate and precise Kalyan Jodi Chart Records. The platform leverages advanced algorithms and a dedicated team to ensure that the information is not only up-to-date but also reliable. As the Matka market evolves, DPBoss adapts, providing users with a reliable compass in their gaming journey. Satta Matka is still very engaging to Indian players and is now amongst the best gambling games in the country. It doesn’t matter if it is Satta Matka 143, Kalyan Matka, or any other form of the game, players from every nook and corner of the country try their luck and strategy. We provide such trends and updates that help assist in the business and Satta matka trends or event live results, news, and analysis of games on our own website.

http://anandinstitutebhopal.com/just-casino-game-review-a-new-zealand-players-perspective/

DPBOSS is a prominent online platform dedicated to Satta Matka, a traditional Indian numbers-based gambling game. Over time, DPBOSS has become synonymous with Satta Matka, offering players real-time updates, expert tips, and comprehensive charts for various markets like Kalyan, Milan, Rajdhani, and Main Bazar . 12:55 PM 01:55 PM Madhur Satta Matka is a popular form of illegal lottery-based gambling that operates across India, combining elements of chance and number prediction. Understanding Madhur Matka requires examining its historical origins, mechanics, legal status, and the significant risks associated with participation. This matka game is very easy to play. You need some simple mathematical calculations knowledge. We Are provide all matka result on time in this page of Raj Ratan Matka

Classement en ligne de casino nous pouvons alors affirmer notre point de vue, le croupier brûlera une carte avant le flop. Le logo Iron Man II est le symbole scatter, le tour et la rivière. En règle générale, il est nécessaire de savoir déchiffrer ce que dit la machine en inspectant la table des gains et la notice. Mais ici, un nom d’utilisateur et un mot de passe permettant d’accéder au site Web sont envoyés par courrier électronique au nouvel utilisateur du Casino par les autorités du Casino. Le navigateur 100% gratuit, rapide, avec VPN intégré Une limite de dépôt annuelle a également été brièvement discutée dans le rapport, chances de frapper la roulette ils offrent des options bancaires fiat mais pas d’options de crypto-monnaie. Pour vous préparer, chances de frapper la roulette leur devise est soit d’aller grand.

https://369clubslot.net/analyse-de-la-popularite-du-jeu-casinia-dans-le-casino-en-ligne-casinia/

Premier boss : Anhuur : Je déteste cette chanson Giana Sisters Twisted Dreams est un jeu de plateforme en 2,5D développé par Black Forest Games et financé par une campagne Kickstarter plus que réussie. À jouer en solo et adapté à toute la famille, il vous demandera du cran, de l’adresse et pas mal de créativité pour en venir à bout. Côté gameplay, c’est du très basique : on saute sur les ennemis et se déplace avec les touches directionnelles, on « charge » et on tournoie en l’air d’une seule touche. Critique publiée par Benoît le 11 02 2014 sur Apps-and-play, site d’actualités et de tests sur les jeux mobiles en activité en 2014 et 2015. Saisissez votre adresse e-mail pour recevoir un e-mail lors de la publication d’un nouvel article sur notre site. C’est gratuit et sans engagement.

Jakość i różnorodność naszych gier to zasługa współpracy z najlepszymi dostawcami oprogramowania w branży iGaming. W Hugo Casino stawiamy na renomowane studia, które gwarantują uczciwą rozgrywkę, innowacyjne funkcje i doskonałą oprawę graficzną. Jesteśmy dumni, że możemy zaoferować naszym graczom tytuły od liderów rynku, co zapewnia nie tylko bezpieczeństwo, ale także dostęp do najnowszych trendów i technologii w świecie gier online. Sloty o tematyce mitologii nordyckiej cieszą się popularnością w szwedzkich kasynach online i zawsze polecam skupienie się na grach, które łączą te elementy epickie historie do życia z bogatą grafiką i satysfakcjonującymi funkcjami. Tytuły takie jak Thunderstruck II, Vikings Go Berzerk i Hall of Gods są wypełnione darmowymi spinami, mnożnikami i rundami bonusowymi, które naprawdę zwiększają Twoje szanse na wygraną. Jeśli lubisz zanurzać się w mitach i legendach podczas gry, te i inne podobne gry oferują ekscytujący sposób na nawiąż kontakt z kulturą nordycką i być może odniesiemy kilka wielkich zwycięstw.

https://global-ops.net/bizzo-casino-recenzja-dla-polskich-graczy-2/

Jesteśmy oficjalnym dystrybutorem firmy MikroTik.Posiadamy status: MikroTik Value Added Distributor. Wchodząc do ustawień urządzenia, a konkretniej do sekcji poświęconej ekranowi, możemy go nieco dopasować pod siebie. W kwestii kolorystyki, do wyboru mamy dwa tryby wyświetlania barw – normalne i wyraziste, przy czym domyślnie ustawione są normalne i wypadają w punkt. Można też dostosować temperaturę barwową, włączyć ochronę wzroku oraz zmienić częstotliwość odświeżania. Prawie wszyscy twórcy automatów mają kilka automatów o wysokim RTP, ale NetEnt i Playtech mają największą liczbę automatów o wysokim RTP. Jeśli musimy wybrać jeden, musi to być NetEnt, ponieważ mają największą liczbę automatów o wysokim RTP. Niektóre z automatów o wysokim RTP oferowanych przez tych deweloperów to Ugga Bugga (99,07%), Mega Joker (99%), Jackpot 6,000 (98,9%) i Blood Suckers (98%).

Book of Dead以古埃及探險為主題,跟隨勇敢的探險家Rich Wilde尋找傳說中的死亡之書。這款5轉輪3排10條賠付線的老虎機,憑藉平衡的遊戲設計和豐富的獎勵機制,成為全球玩家的最愛之一。 Q5:老虎機攻略重點是什麼?→ 理性控制投注、理解機制、善用 Buy 功能機會,就是高勝率的關鍵! 歡迎來到 AlphaCard,您在台灣信用卡領域最值得信賴的專業平台。在這個消費多樣、回饋複雜的時代,我們致力於為您提供最清晰、最客觀的信用卡資訊,無論您是信用卡新手或資深玩家,都能在此找到最適合您的刷卡攻略。 老虎機介紹 在2025年的線上老虎機遊戲中,免費旋轉絕對是玩家最愛的福利之一!這種機制不僅能讓你「零成本」體驗老虎機的刺激感,還能大幅提升贏得累積彩池的機會。究竟免費遊戲是怎麼觸發的?又該如何最大化利用?這篇攻略將深入解析最新趨勢與實用技巧。

https://b.io/rempchartvingla1986

樂遊石虎國王溫馨提醒: 在樂遊娛樂城玩《奧林匹斯之門™》還能順便解每日任務拿獎勵! 在奧林匹斯之門《Gates of Olympus™》中,每個符號的賠付計算方式都是根據符號出現的數量以及其對應的賠率來決定的。以下是一般的計算邏輯: 奧林匹斯之門《Gates of Olympus™》結合了古希臘神話的神秘魅力與現代賭場遊戲的創新機制,打造出一款令人難以忘懷的老虎機遊戲。從精美的視覺效果、流暢的動畫表現,到獨特的符號系統和多變的獎勵模式,每一個設計細節都旨在提升玩家的沉浸感與獲勝樂趣。 「奧林匹斯之門1000」的畫面和音效相輔相成,不僅展現古希臘神話的壯麗,也通過生動的動畫特效和激昂的音樂強化了遊戲的沉浸式體驗,不論是視覺還是聽覺都能讓玩家感受到神話世界的震撼。

Another exciting online slots feature of Aloha! Cluster Pays is the Sticky Win Re-Spins feature, which is activated randomly after a win. This means all the clustered symbols remain in place while the other reels spin. Since the aim of the game is to add more symbols to existing clusters, this could lead to some big wins, as the spinning reels land on symbols that could potentially add to the existing cluster. Now you know a bit more about Aloha! Cluster Pays, we hope you give the reels a spin, and have some fun as you kick back and nuzzle your toes into the soft Hawaiian sands! The absence of a traditional free spins round in “Aloha Tiki Bar” sets it apart from other slots, relying instead on the engaging respin feature activated by Wild symbols. This deviation from the norm adds an element of unpredictability and keeps players on the edge of their seats as they chase those coveted big wins.

https://www.studio-diporto.com/casino-jax-slot-review-a-thrilling-experience-for-australian-players/

Aztec Fire 2 is a 5-reel, 3-row video slot with 25 fixed paylines. The minimum bet is $0.25 per spin, while the maximum bet goes up to $125 per spin. The slot features colorful Aztec-themed symbols like jewels, totems, snakes, and card suit icons. The wild substitutes for other symbols to form winning combinations, except for the scatter and bonus symbols. Landing 3 or more scatter symbols triggers the free spins feature with increasing multipliers up to 5x. During the base game, the slot also has a random bonus picker feature which gets triggered occasionally and awards cash prizes, multipliers, or free spins. Next, each with an associated number. If you would like to claim a No Deposit Bonus, aztec fire game you can try your hand at Dream Catcher. When you play this slot machine you can get more free plays as well as more money from the jackpot prize, Super Sic Bo.

Uma boa maneira de saber se a experiência de apostas no cassino é agradável antes mesmo de criar uma conta é experimentar as versões demo grátis dos melhores jogos. Assim, você não compromete seu orçamento e pode testar a navegabilidade do site. Vale a pena conferir a demo também pelo celular para saber como é a otimização do cassino. Nota: Se você gosta de Gates of Olympus, pode jogar outros caça-níqueis semelhantes no modo de demonstração no Templo de Slots. Experimente outros jogos de cassino da Pragmatic Play, outros caça-níqueis online gratuitos ou outros jogos de cassino com tema mitológico. A versão demo da Gates of Olympus permite jogar numa das slots mais icónicas da Pragmatic Play sem riscos. Com o monte olimpo como pano de fundo, símbolos alusivos a Zeus e mecânicas únicas, este formato de demonstração é a escolha ideal para testar e conhecer a slot.

http://www.haxorware.com/forums/member.php?action=profile&uid=430285

Existe uma estratégia para buscar renda extra mensal média de R$ 900 a até R$ 9 mil com bitcoin; veja como pessoas comuns podem investir Embora os jogos de slots sejam os grandes favoritos online, os jogos de casino mais clássicos são, sem dúvida, os jogos de cartas e de mesa que você encontrará em estabelecimentos de casino físicos. Portanto, você também encontrará jogos como roleta grátis, blackjack grátis, e muito mais aqui em nosso site. Dessa forma, você pode facilmente familiarizar-se com esses jogos online ou apenas desfrutar da jogabilidade sem gastar dinheiro. Uma das melhores características é a imprevisibilidade, visto que o primeiro corte já pode revelar altos ganhos. A possibilidade de também perder a qualquer momento ou de ter os ganhos cortados com um doce de pouco valor faz com que um jogo simples seja emocionante! Então, se estiver cansado da mesmice de sempre, Ninja Crash é um bom jogo para recomeçar!

**mounja boost official**

MounjaBoost is a next-generation, plant-based supplement created to support metabolic activity, encourage natural fat utilization, and elevate daily energywithout extreme dieting or exhausting workout routines.

Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Tennessee, Washington, and West Virginia. The game has five reels and 20 paylines at your disposal, and to start playing it, you will need to select one of the casinos that are located on the side of this article. Choose the one with the best promotion and the one that suits you the most to enjoy your gaming more. Jack and the Beanstalk slot has an RTP of 96.30% and you can start your spins with as little as 0.01 coin value. The Jack and the Beanstalk slot’s bonus features play a significant role in amplifying potential winnings. Features like walking wilds and free spins can significantly increase players’ chances of hitting more substantial wins. Engaging with these features strategically, understanding their mechanics, and capitalising on them can make the gameplay more exciting and rewarding.

https://mielflordelaalpujarra.com/discovering-sports-games-at-spinit-casino-australia-a-unique-review-interview/

Bigger Bass Bonanza, developed by Pragmatic Play, is the upgraded and more premium version of the classic slot game Big Bass Bonanza. With higher betting options, it’s designed to cater to high rollers looking for big prizes and a more engaging fishing-themed experience in online casinos. Big Bass Bonanza uses a fishing theme, with the reels floating just below the ocean’s surface. Blue depths are the game’s background scenery, filled with fish, seaweed, and bubbles. The online slot has a nice funky tune as its soundtrack, setting a perfect atmosphere for an adventure on the open sea. Graphics are brightly-coloured, crisp and well-executed. The fishing theme in online slots has always captivated players, and Big Bass Bonanza Slot truly takes this excitement to an entirely new level. Set against the backdrop of serene lakes and the thrill of catching massive fish, this slot game offers an enticing blend of fun, adventure, and potential rewards. With its casual vibe and engaging mechanics, players are bound to reel in some wins while enjoying the peacefulness of nature.

After facing a reel of treasures, players can try to gain access to the heaven-like Olympus. Escaping into a world of myth and magic will be an adventure. That will be true whether the player makes it to the top of Mount Olympus or are cast down into Hades. You’ll discover rings, crowns, and an hourglass on the 6×5 grid, while lower-value symbols include sparkling gems of various shapes and sizes. The most powerful Greek god of all, Zeus, appears as a bonus symbol, and he’s also floating around behind the reels, in the mythical seat of the gods. Gates of Olympus game settings also allow some useful controls such as turning on and off Quick Spin, Battery Saver, Ambient Music, Sound FX, and Intro Screen. Within the settings window, you’ll also have a chance to adjust the total bet and view Game History. But the latter isn’t available when you play the game in demo mode.

https://www.dbx-look.pt/review-of-kats-casino-an-online-casino-hub-for-australian-players/

Follow the signs to The Theatre from the underground parking. If arriving from the parkade, The Theatre can be accessed through the gaming floor.For all ages access when arriving from the east entrance (parkade or main entrance), proceed to the hotel lobby elevators to reach level 2. From there, simply follow the signage directing you to the Theatre. Guests of all ages may also enter The Theatre via the west entrance or from the underground parking lot. 15 dragon pearls the third highest hand is four of a kind, they offer markets not just for major team sports but also for niches like cornhole. They also have a low minimum deposit requirement of just $10, and we also suggest you play Ghost Pirates by Netent. Get to know the game range and the beautiful slots. Have any questions about our company & our products!

Seja pelo celular ou no computador, a F12bet oferece uma experiência dinâmica de apostas com páginas que carregam rapidamente e mais de 1.500 jogos de provedores como Pragmatic Play, PG Soft e Hacksaw Gaming, a maioria com recurso de free spins. O Gates of Olympus 1000 Demo é um jogo excelente que faz jus ao legado do primeiro slot da franquia. Franquia essa tão popular que chega a ser difícil encontrar um cassino que não ofereça pelo menos um dos seus títulos. Na Betclic, pode jogar 6 edições da slot: Gates of Olympus Original, 1000, Xmas 1000, Super Scatter, Betclic 1000 (exclusivo) e Hades. Cada uma tem RTP e volatilidade semelhantes, mas diferenças nos multiplicadores e prémio máximo. A PragmaticPlay (Gibraltar) Limited é licenciada e regulamentada na Grã-Bretanha pela Gambling Commission sob o número de conta 56015 e licenciada pela Gibraltar Licensing Authority e regulamentada pela Gibraltar Gambling Commissioner, sob o RGL No. 107.

https://cursos.institutofernandabenead.com.br/?p=693879

Na Solverde.pt, há de tudo: ofertas relâmpago, promoções semanais e ainda ofertas permanentes, como as de boas-vindas para novos jogadores. This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data. Dica extra: em horário comercial, também dá para tirar dúvidas via telefone 0800 se a plataforma oferecer, como a Esportivabet. This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

“Lots of games and super fun leaderboards.” Tags :Aloha ChristmasChristmasCluster PaysmobileNetEntvideo slots Online Slot Games For Fun I started my Aloha Tiki Bar slot machine with 100 spins with a minimal bet of $0.50. During the first rounds, I needed clarification about the mechanics. However, after 15 spins and with the help of the payline menu, I quickly understood them. Moreover, I hit a small profit of $25. Play Tropical Tiki slot online and unmask an exciting game with big prizes, a tumbling reels feature, and free spins with extra rows and 6,400 ways to win. Spin this hot slot for free or play Tropical Tiki for real money at the best online casinos and win up to 3,000x your bet. Wild symbols in the Aloha Tiki Bar slot machine substitute for all other symbols and appear only on reels 2, 3, 4, and 5. Wild symbols on the screen will expand over the reel, triggering a free respin. These Wilds remain sticky throughout the free respin series, which play automatically at the same bet level as the game in which they were triggered.

https://flipanybusiness.com/level-up-casino-review-fast-payouts-top-gaming-experience-for-australian-players/

Aloha Clusters Pays has a Hawaiian theme, with the background, characters and symbols having been designed to emulate the bright colours you’d expect to see in Honolulu or Oahu. Aloha! Cluster Pays introduces an innovative Cluster Pays mechanism that sets it apart from traditional online slots. Rather than forming winning combinations on paylines, players win by landing clusters of nine or more matching symbols. To get a better idea about the game, feel free to play Aloha! Cluster Pays for free in demo mode with no download and no registration required and decide whether you want to play this slot machine for real money in a casino. Because of the way the slot machine functions, trying to keep track of your wins can be quite difficult at first. The only other negative point we can really think of is the fact that they’re not so many Cluster Pays slots available to play at the moment.

En initiativ, vi har sat i søen med henblik på at etablere et globalt selvudelukkelsessystem, der giver sårbare spillere mulighed for at blokere deres adgang til alle former for onlinespil. tilbyder øjeblikkeligt spilbare mobile websteder , hvilket betyder, at du kan spille Gates of Olympus Dice Demo direkte fra din browser uden at downloade en app. Dette er en praktisk alternativ for dem, der foretrækker ikke at installere yderligere software. “Selvfølgelig! Du kan prøve Gates of Olympus 1000 Dice spilleautomaten i demo-version lige her hos BETO Spilleautomater før du sætter rigtige penge på spil. Det er perfekt, hvis du vil lære spillets mekanik og bonusfunktioner at kende uden økonomisk risiko.\r\n” Spillemaskinen fungerer perfekt på alle enheder. Download vores mobil casino app, så du kan spille Gates of Olympus, hvor og når det passer dig.

https://hayloftshropshire.co.uk/2026/02/09/nv-casino-anmeldelse-din-guide-til-spiloplevelsen-i-danmark/

En initiativ, vi har sat i søen med henblik på at etablere et globalt selvudelukkelsessystem, der giver sårbare spillere mulighed for at blokere deres adgang til alle former for onlinespil. Hvis du gerne vil øge dine vinderchance i Gates of Olympus spillet, så er her et par tips og tricks, der vil hjælpe dig i gang med at optimere dit gameplay i Gates of Olympus spillet: Så hvis du vil spille mobil spillemaskine på din smartphone, der er værd at nævne. Dette gælder især i eSport-sektionen, ved hjælp af denne betaling udbyder sikrer fremragende sikkerhed. Kan jeg spille Take Olympus Slots for rigtige penge, mens franske og europæiske variationer har et enkelt nul. De fleste sider accepterer Paysafecard som betalingsmetode, Roulette og Video Poker alle arbejde præcis som youd forventer dem til. Disse funktioner kan fås via din kontosektion eller ved at komme i kontakt med kundesupport, skal vi først forklare reverse bets. Mange spillemaskiner tilbyder forskellige bonusser og tilbud, et online bingoside.

The Aloha Cluster Pays slot isn’t your typical slot. There are six reels and five rows, but you won’t find the usual paylines here. Instead, what you have are clusters. This means that there is no left to right matching of symbols: you can match the symbols in a whole manner of ways, and this increases your chances of winning. Aloha Cluster Pays is one of the newest video slots by NetEnt. It was developed and then introduced in March of 2016. The company is considered to be one of the top providers of digital gaming software. The Aloha slot game has no offline predecessors and is a unique development that is available to play on multiple systems and devices—PCs, tablets, and mobile phones. Aloha! Cluster Pays Although this innovative concept was NetEnt’s brainchild, many game developers have since embraced the Cluster Pays mechanic. Today, we have a huge range of Cluster Pays slots with unique themes, features, and gameplay.

https://www.cnss.cg/2026/02/11/planet-7-oz-casino-review-a-stellar-choice-for-australian-players/

Gambling companies must provide rules for each of their products. Different types of companies may also need to provide players’ guides to their games. For example, a casino must offer a player’s guide to the house edge, while an online gambling company must provide a player’s guide to each gambling product (bet, game or lottery) that they offer. You should make sure you understand the rules before you start to gamble. If you feel that the instructions provided weren’t clear, you may be entitled to make an appeal according to the Consumer Rights Act (2015). When a new casino applies, the UKGC checks everything—financials, who’s running things, and the tech setup. Always read the terms and conditions – many bookmakers will demand that a deposit is made in exchange for the bonus. The Gambling Commission believes that you should be able to get your money back out in the event that you don’t want to gamble. If you find that you can’t do this, you should use Resolver to launch a complaint.

– Sabrina Erhalten Sie Neuigkeiten und spezielle Angebote Hauptkategorien Registrieren Sie sich für unseren Newsletter, bleiben Sie über alle Angebote und neuen Produkte informiert. Wilde Erdbeere als Geleebonbon Sauer – Verkauft in großen Beuteln von 1 kg Mezzo Mix steht nicht nur für unbeschwerten Genuss, sondern auch für „Made in Germany“. 97 Prozent der in Deutschland verkauften Coca-Cola Getränke werden hier produziert – in 13 Produktionsbetrieben im ganzen Land. Genau wie ViO und die ViO Bio Limo ist auch Mezzo Mix eine in Deutschland erfundene Marke. Diese tiefe Verwurzelung zeigt, dass Deutschland für Coca-Cola wichtig ist – und Coca-Cola für die Menschen, die in Deutschland leben. WINNER: Travel Brand of the Year Beispiele: TalkWalker, SparkToro, Meltwalter Großer Plastikkürbis, gefüllt mit eingewickelten Süßigkeiten, die zum Thema Halloween dekoriert sind.

https://tvchouf.com/online-slots-bei-mostbet-de-grose-auswahl-und-hohe-gewinne-review/

Neben der Verschlüsselung der Daten ist auch die Sicherheit der Zahlungsmethoden ein wichtiges Thema, die kostenlose Spins anbieten. Live Roulette ist eine der aufregendsten Formen des Online-Glücksspiels, wie klassische 3-Walzen-Slots. Sie haben oft mehrere Walzen und Gewinnlinien, Video-Slots. Einige Casinos erheben Gebühren für Einzahlungen, ohne allzu großen Aufwand ins Spiel zu kommen. Im Basisspiel wird einiges geboten bei Book of Toro. Wenn mindestens zwei Mumien erscheinen, wird ein Mummy Re-Spin gestartet. Die Mumien bleiben dabei auf den Walzen. Wenn eine weitere Mumie kommt, gibt es einen weiteren Mummy Re-Spin. In jedem Fall enden die Mummy Re-Spins, wenn ein Toro auf den Walzen erscheint. You can email the site owner to let them know you were blocked. Please include what you were doing when this page came up and the Cloudflare Ray ID found at the bottom of this page.

O catálogo da Mostbet inclui também concursos de televisão com elementos interativos. Todos os espetáculos ao vivo estão numa secção própria no website do casino Mostbet. Já escolheu o seu jogo preferido? O website da Mostbet foi pensado com as cores da marca: azul e branco. O logótipo Mostbet está no canto superior esquerdo. Logo acima, no painel superior, encontrará links para a aplicação, fuso horário, hora atual e definições de idioma. Também há uma secção de bónus e promoções, e botões para se registar ou iniciar sessão. Abaixo, encontra-se o menu principal, com as secções que a Mostbet oferece: O website da Mostbet foi pensado com as cores da marca: azul e branco. O logótipo Mostbet está no canto superior esquerdo. Logo acima, no painel superior, encontrará links para a aplicação, fuso horário, hora atual e definições de idioma. Também há uma secção de bónus e promoções, e botões para se registar ou iniciar sessão. Abaixo, encontra-se o menu principal, com as secções que a Mostbet oferece:

https://www.franciscosales.co/2026/02/05/aposta-ivibet-cassino-login-tutorial-para-acesso-rapido/

O governo de El Salvador havia anunciado que usaria o dinheiro dos Volcano Bonds para financiar vários projetos de infraestrutura, incluindo a construção de infraestrutura para a mineração de Bitcoin, o desenvolvimento de uma “cidade Bitcoin” no país e outros projetos relacionados à adoção do Bitcoin. A Mostbet, tanto o casino como a casa de apostas, possui uma licença de Curaçao. Esta licença é reconhecida internacionalmente. Ela permite que a Mostbet organize jogos de azar e apostas desportivas em várias partes do mundo. Desta forma, Mostbet segue as normas globais da indústria. Mostbet assegura um ambiente de jogo seguro e transparente para si. O cassino online é operado pela Dama N.V, uma empresa renomada no mundo dos jogos online, além de possuir licença de Curaçao. Como o primeiro cassino multimoeda a aceitar, não apenas moedas tradicionais, como Dólares e Euros, mas também Bitcoin e outras criptomoedas, a Bitstarz tem uma reputação sólida e é respaldada por anos de experiência.

You can play Bigger Bass Bonanza on any mobile device on MrQ. Sign up today and play over 900 real money slots and casino games. Big Bass Bonanza 1000 plays it safe, but bigger jackpot fish and a boosted win cap give the familiar formula a welcome lift. In the Big Bass Bonanza online slot, the free spins feature plays a crucial role in hitting the slot’s biggest payouts. Landing three, four, or five scatter symbols will activate the round. Depending on the number of scatters, you’ll be awarded 10, 15, or 20 bonus spins. Bigger Bass Bonanza takes you Miami for more paylines, the same high RTP rate and Free Spins feature but with much higher win potential (4,000 x bet) compared to Big Bass Bonanza. Big Bass Bonanza Megaways- More fish than ever as Big Bass Bonanza is back with over 46,000+ ways to win. Big Bass Bonanza Megaways ups the ante with 6 reels of fishin’ frenzy and an upgraded max win of up to 4,000x your total bet. The fish is back and, this time, there’s plenty more of them in the lake.

https://aquatech-group.com/roospins-casino-free-bets-available-in-australia-review/

Big Bass Bonanza is a popular Pragmatic Play slot that offers exciting fishing-themed gameplay with high volatility and a 96.71% RTP. While slots are based on luck, here are general tips to enhance your chances of winning at this slot: Big Bass Bonanza features a symbols designed around its fishing theme. Each symbol has a specific payout value, which depends on the number of symbols matched on a payline. Our web site provides UK players with access to the full paytable, helping you plan your gameplay efficiently. Set on the ocean, Big Bass slot games follow a fisherman on his adventures as he tries to reel in prizes. Gamesys Operations Limited is licensed and regulated in Great Britain by the Gambling Commission under account number 38905, in Gibraltar by the Government of Gibraltar and regulated by the Gibraltar Gambling Commissioner (RGL No. 46 and RGL No. 153), and in Ireland by the Office of the Revenue Commissioners under licence reference 1021538.

As a leading supplier of online gambling content in regulated markets worldwide, we place game integrity and player safety at the heart of everything we do. Multipliers can hit on any reel during the base game and leave behind values ranging from 2x – 1,000x which are combined at the end of a every spin and awarded to players. Betting ranges from R0.20c up to R600 per spin, with a max win of 15,000x your bet and an RTP of 96.40%. The game offers very high volatility for an exciting experience. Be warned though – It’s difficult to hit a max win on the original game – expect this to be 3 x harder! Check out some big wins on Gates of Olympus on our YouTube Channel. London.bet is a trading name of Thistle Bet Limited, a company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 16120667. Registered office: 2 Alexandra Gate, Cardiff, CF24 2SA, United Kingdom. Thistle Bet Limited is licensed and regulated in Great Britain by the Gambling Commission under account number 66162.

https://personalizeseutreino.com.br/beep-beep-casino-review-for-new-zealand-players/

If you’re a fan of the original slot, you’ll spot the original formula with a few expanded features designed to increase both pace and payout potential. Below, you’ll find a breakdown of the core mechanics that define the gameplay of the Gates of Olympus 1000 online slot. If you enjoy Greek-themed slots or straightforward high-risk mechanics, the Gates of Olympus game offers powerful visuals, cascading wins, and multiplier-boosted free spins that keep every round intense. As a leading supplier of online gambling content in regulated markets worldwide, we place game integrity and player safety at the heart of everything we do. When you see Zeus guarding the gates and holding his lightning sword, you know you’ve reached the Gates of Olympus. In the background, you’ll see Greek architecture where Ancient Greece’s most important gods reside. And at the foreground, you have the reels filled with symbols fitting the Greek Mythology theme.

The statistical chances of winning in the Gates of Olympus slot game are determined by the game’s software and the specific online casino platform offering the game. The exact odds and payout percentages may vary. 4, 5 o 6 simboli Scatter pagano un premio e attivano i Free Spins. It seems great and contains an encouraging sound recording that participants will delight in. Those trying to earn particular huge jackpots yes find a way to do so to play this video game. Doorways from Olympus is roofed on the directory of games that have a SpinBlitz progressive jackpot. The more the game is played as well as the jackpot isn’t claimed, the higher they grows. Pragmatic Enjoy always supplies higher-looking slot online game. Gates away from Olympus suits you to bill, with easy graphics and you may an awesome Ancient greek motif.

https://thepizzamia.com/recensione-amunra-lemozione-dellantico-egitto-in-un-click-per-i-giocatori-italiani/

Gates of Olympus con un RTP di 96.50% e un posizionamento al 560 è un’eccellente scelta per i giocatori che apprezzano un rischio moderato e vincite costanti. Questo RTP garantisce stabilità senza forti oscillazioni. La volatilità elevata di Gates of Olympia 1000 rende questa slot un’opzione invidiabile per le nostre strategie preferite alle slot machine, che mirano infatti alla massima volatilità possibile. In questo caso, e così. Il giocatore dalla Danimarca ha avuto il suo ritiro respinto senza ulteriori spiegazioni, tutti i tuoi dubbi sulla sicurezza e la sicurezza dovrebbero essere messi a riposo. Essere pagati rapidamente è molto importante per molti giocatori di casinò online là fuori, ma uno svantaggio è loro leggermente limitata giochi di casinò dal vivo. Ora, ci sono due vantaggi chiave quando si gioca con cryptocurrencies. Inoltre, Clemson ha quasi battuto Duke on the road all’inizio di quest’anno 71 a 69.

Lors du lancement de Sugar Rush 1000 gratuit, le joueur verra un écran d’accueil présentant les principales caractéristiques de cette machine à sous en ligne. Une animation simple montre le déclenchement des Free Spins ainsi que le fonctionnement des Sticky Multipliers ; le joueur pourra également prendre connaissance de la volatilité et du max win Sugar Rush 1000 – x25 000. Cet écran d’information peut être désactivé lors des parties suivantes en appuyant sur un bouton dédié. Intel est une marque déposée d’Intel Corporation ou de ses filiales. Windows est une marque du groupe d’entreprises Microsoft. L’ambiance musicale est totalement en accord avec l’univers du jeu. Lorsque le joueur fait tourner les rouleaux de la version demo de Sugar Rush 1000 ou place des mises réelles, une mélodie joyeuse accompagne les parties. Les combinaisons gagnantes disparaissent de l’écran avec le son de bulles éclatées, tandis que le déclenchement du jeu bonus est marqué par une sirène. Pendant les Free Spins, le design du jeu passe à une version nocturne et la musique devient plus dynamique.

https://urbanrepairing.com/jeux-du-penalty-shoot-out-une-experience-immersive-par-evoplay/

Redécouvre les classiques comme le Monopoly ou la Roue de l’argent en live en ligne et profite des versions casino de tes jeux télévisés préférés sur jackpots.ch. La meilleure façon de se lancer sur Gates of Olympus pour “de vrai” est avec un bonus. Sans surprise, les meilleurs viennent des offres de bienvenue des casinos en ligne avec des tours gratuits ou des mises remboursées. Assurez-vous néanmoins de vérifier les exigences de mise et surtout, si le bonus d’un casino est éligible à Gates of Olympus. La machine à sous Gates of Olympus 1000 vous ramène dans le monde de la mythologie grecque antique. Cette machine à sous offre une disposition 6×5 avec un mécanisme de paiement partout. Elle utilise la fonction Tumble pour des gains répétés en un seul tour. Parmi les points forts, citons les symboles multiplicateurs valant jusqu’à 1 000 fois et les tours gratuits qui augmentent les gains, ainsi que l’option d’achat de bonus qui permet de se lancer directement dans l’action lucrative.

The return to player (RTP) for this slot is slightly above average; the Gates of Olympus RTP comes in at 96.5%. RTP is critical with games like this one that are considered highly volatile. Luckily, Gates of Olympus has a decent RTP to combat the risk of its volatility. Spin your office chair around a few times before peering at the screen, and it might be tough to tell which version of Gates of Olympus you’ve got, as Gates of Olympus, Gates of Olympus 1000, and now Gates of Olympus Super Scatter share a similar appearance. A big 6×5 matrix takes up most of the space, bordered by a celestial representation of Olympus in the background with Zues on one side. It’s a fine view, very in theme, and familiar at the same time. As players approach the base of the Gates of Olympus at Foxy Games, they feel the thrill of adventure building inside us. The mountain looms before them; its peak shrouded in mist and mystery. It’s a daunting challenge, but players are on a quest to unlock the ancient secrets and treasures that lie within.

https://industrialswebs.com/aviator-in-kenya-quick-review-and-player-perspectives/

You can also try the Gates of Olympus demo slot without creating an account. Once you’re ready to play for real money, CoinCasino supports instant crypto payouts and regular weekly promotions worth up to $100,000. Their platform is simple to navigate, and gameplay runs smoothly on both desktop and mobile devices. Players will find themselves at the entrance to the realm of the Gods, Olympus. An ominous Zeus hovers at the gate, daring those who approach to be worthy. Something’s missing. Jackpots, slot gates of olympus by pragmatic play demo free play while the right half of the screen has the live casino games. The dropping wilds in the Legend of Elvenstone will have three character power-ups, whenever theres a winning combination youll get the winning symbols removed from the reels. Now that we’ve covered the game, let’s look at the best Gates of Olympus casinos where you can play it. These gambling sites all offer Gates of Olympus free play, real money gaming, and strong bonuses. The table below highlights the key offers before we dive into each review.

Plinko Australia dispone di una comoda tabella. Si trova sul lato sinistro dello schermo e fornisce dati sui risultati dei turni passati. Per ottenere le vincite massime, è necessario giocare a Plinko con una volatilità elevata. I giocatori possono anche utilizzare i codici promozionali del casinò mentre si divertono con il gioco Plinko sui loro smartphone. Mystake Casino offre spesso ai suoi affezionati giocatori premi come Free Spins o Freebets che possono essere utilizzati nei suoi esclusivi mini-giochi come il gioco Plinko. Plinko casino è ottimizzato per i actually dispositivi mobili,” “conseguentemente potete lanciare la pallina e godervi il gioco dove e quando volete, direttamente dal vostro smartphone o tablet. Come abbiamo pasado, i bonus pada benvenuto possono alterare notevolmente tra we casinò. Le Plinko recensioni che abbia sul nostro sito sono genuine electronic redatte direttamente dal nostro team di esperti. Ogni affiliato del nostro staff members che scrive la recensione su este qualsiasi gioco di casinò testa within prima persona my partner and i giochi, analizza the fondo tutte votre sue caratteristiche at the ne verifica una disponibilità nei casinò ADM.

https://boldbd.org/sugar-rush-dolcezza-e-vincite-recensione-per-giocatori-in-italia/

Eseguiamo dei controlli sulle recensioni Come è evidente dalla tabella, chiunque voglia giocare a Plinko a soldi veri ha un’ampia scelta. Troviamo moltissime opzioni tra cui scegliere come Plinko Go e Plinko Dare to Win, che sono le più frequenti. Ma troviamo anche bonus Plinko proposti dai casino online. Nella lista dei siti più affidabili, abbiamo considerato solo i contesti dove il gioco è legale e regolamentato secondo la normativa italiana dei Monopoli di Stato. In questo caso è garantito da ADM che l’RNG, l’algoritmo che determina casualmente le vincite, sia affidabile e certificato. Betflag è uno di quegli operatori al top quando si tratta di giochi e slot disponibili per i propri clienti. Sono davvero tantissimi i titoli disponibili, per questo è bene sapere dove cercare. Le due versioni di Plinko presenti sul sito, si trovano infatti in due aree differenti. Quella di 1x2Gaming è localizzata dento la sezione “Slot”, dove consigliamo di digitare il nome del gioco nella barra di ricerca. Spostandosi nella sezione “Games”, nella barra in alto del menù, sarà possibile trovare Plinko di Hacksaw. A differenza di altri operatori, quindi, Plinko sarà presente dentro l’area “Casinò”.