Bangladesh stands at a dangerous crossroads where the rituals of democracy remain intact, but its substance is being systematically hollowed out. What is unfolding is not merely an imperfect election cycle, but a profound crisis of legitimacy—one that implicates the Election Commission, the political administration, security agencies, and the silent empowerment of extremist actors under the cover of political expediency.

At the centre of this crisis lies an Election Commission whose credibility has been irreparably compromised. The Commission’s inability—or unwillingness—to complete a credible, inclusive, and accurate voter roll is not a technical failure; it is a political one. Reports of missing names, arbitrary exclusions, and flawed registration processes disproportionately affecting minority communities raise grave concerns of deliberate disenfranchisement. When minorities are intimidated, threatened, or subtly coerced into abstaining from participation, the electoral process ceases to be free and fair, regardless of how efficiently ballots are cast on polling day.

Equally alarming is the political context in which these elections are being staged. The non-participation of the country’s oldest and most historically significant political party is not a footnote—it is an indictment. Elections without meaningful competition are exercises in administrative choreography, not democratic choice. The mass arrests and arbitrary detention of opposition leaders and activists have created an atmosphere of fear that fundamentally undermines political pluralism. When leaders are imprisoned, party offices sealed, and supporters harassed, the right to contest power becomes theoretical rather than real.

This erosion extends beyond political parties into the civic space itself. Freedom of association, peaceful assembly, and expression—cornerstones of any functioning democracy—have been systematically curtailed. Public gatherings are restricted or denied permission, protests are met with force, and dissent is equated with sedition. Such measures are not designed to maintain order; they are intended to suppress visibility, coordination, and resistance.

The media landscape tells a similarly bleak story. Journalists and media houses face relentless pressure through legal harassment, intimidation, financial strangulation, and selective enforcement of draconian laws. Investigative journalism has become a high-risk profession, while self-censorship has become a survival strategy. When the press is silenced or domesticated, elections become exercises in managed perception rather than informed consent.

Civil society organisations and human rights defenders—traditionally the moral conscience of the state—are facing unprecedented restrictions. Regulatory harassment, funding constraints, surveillance, and public vilification have rendered many organisations ineffective or silent. A democracy that fears its own civil society has already crossed the threshold into authoritarianism.

Perhaps most damning is the state’s failure to protect religious and ethnic minorities. Attacks on minority communities, places of worship, and livelihoods are often met with delayed responses, inadequate investigations, or complete impunity. In some cases, victims are pressured into silence or compromise. This selective blindness not only emboldens perpetrators but signals that citizenship itself has become conditional.

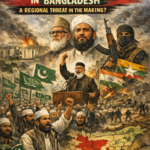

Compounding this moral collapse is the growing presence of Jamaat-e-Islami affiliates within the administrative ecosystem and their alarming proximity to influential figures, including Yunus-linked circles. This is not a matter of ideological diversity; it is a question of legitimacy and security. Jamaat’s historical opposition to Bangladesh’s Liberation War, its documented role in war crimes, and its continued rejection of secular constitutional principles make its quiet rehabilitation deeply destabilising.

Even more troubling are persistent allegations regarding Jamaat’s illegal financial networks and their links to extremist groups operating domestically and transnationally. These networks—often masked through charities, businesses, and informal financial systems—pose a direct threat to national security. The absence of decisive state action suggests either complicity or political calculation.

Jamaat’s historical and ongoing links with Pakistan, and the alleged involvement of foreign agencies seeking to reshape Bangladesh’s political trajectory, cannot be dismissed as paranoia. In a region marked by hybrid warfare, influence operations, and ideological radicalisation, such alignments carry serious implications. When foreign interests converge with domestic extremist agendas, sovereignty itself becomes negotiable.

The cumulative effect of these developments is a rapid deterioration of communal harmony. Bangladesh’s founding promise—secularism, pluralism, and dignity for all—has been steadily replaced by polarisation, fear, and identity-based mobilisation. Jamaat-e-Islami’s role in exploiting grievances, inflaming sectarian narratives, and positioning itself as a political beneficiary of chaos is unmistakable.

What emerges from this landscape is not an isolated failure but a systemic one: an election without trust, participation, or protection; a state that governs through coercion rather than consent; and a political order that tolerates extremism while criminalising dissent. History is unforgiving to such experiments. Democracies do not collapse overnight; they erode slowly, bureaucratically, and often legally—until one day the façade remains, but the republic is gone.

Bangladesh is perilously close to that moment.