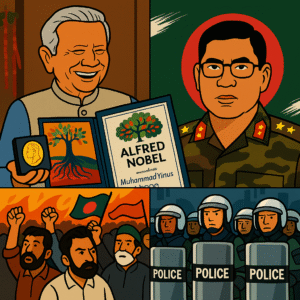

In Bangladesh, the line between politics and power has always been porous. But the events unfolding in 2025 suggest we’re entering a new phase—one where the military flexes with impunity, the civilian government stands on borrowed time, and the Islamist street is rumbling back to life. The latest flashpoint? A very public show of force by the Chief of Army Staff, rebuking the Interim Government’s unilateral move to allow a UN humanitarian corridor into Myanmar’s Arakan region. That diplomatic decision, made without military or parliamentary backing, opened the floodgates. The Army Chief didn’t just question the move—he practically issued an ultimatum, demanding elections by December 31, 2025.

In Bangladesh, the line between politics and power has always been porous. But the events unfolding in 2025 suggest we’re entering a new phase—one where the military flexes with impunity, the civilian government stands on borrowed time, and the Islamist street is rumbling back to life. The latest flashpoint? A very public show of force by the Chief of Army Staff, rebuking the Interim Government’s unilateral move to allow a UN humanitarian corridor into Myanmar’s Arakan region. That diplomatic decision, made without military or parliamentary backing, opened the floodgates. The Army Chief didn’t just question the move—he practically issued an ultimatum, demanding elections by December 31, 2025.

But the deeper fault line isn’t about Arakan. It’s about who really runs Bangladesh, and who might take it over next.

The Corridor That Cracked the Facade

Granting access to the UN to deliver humanitarian aid through southeastern Bangladesh might have been a practical move on paper. But in a region hypersensitive to sovereignty and foreign involvement, it was political TNT. The military saw it as a breach of protocol—and more importantly, as a strategic opportunity.

By casting the Interim Government as weak, reckless, and out of touch, the Army Chief reasserted the military’s traditional self-image: guardian of the nation, not just its borders. This power play—barely masked behind calls for electoral stability—has re-injected the military into the political bloodstream, just as Islamist forces begin to stir again.

Remember July-August 2024?

The so-called student quota protests began as a classic grassroots movement: young people protesting an outdated, inequitable system of government job reservations. But what started as a civic issue was hijacked—quickly and methodically—by Islamist forces. Within weeks, Dhaka’s campuses were echoing slogans less about reform and more about religious revival. Madrasa students joined en masse. Clerics lent their pulpits. What looked like another middle-class reform protest morphed into a pseudo-Islamist insurrection.

And it worked. The Hasina government, already worn down by internal dissent and external pressure, collapsed. The army refused to intervene. The streets did the job.

A Looming Counter-Revolution?

The echoes of 2024 are growing louder. The convergence of military assertiveness, an unelected government’s perceived illegitimacy, and international presence in a sensitive border region has recreated the perfect conditions for a counter-revolutionary storm.

But this isn’t a replay of 2007. This time, the ideological momentum is heavier. Groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT), Jamaat-e-Islami, and Hefazat-e-Islam aren’t just waiting—they’re planning. The new alignment isn’t just anti-government; it’s anti-system. Their pitch is simple: the state has failed, only Islam can restore justice and sovereignty.

The student movement proved how quickly a populist fire can spread when it taps into moral outrage and national insecurity. The Arakan corridor may serve as a new rallying cry. A foreign footprint on national soil. A secular government playing globalist games. It’s fertile ground for a movement that sells divine order over democratic disorder.

Elections or Explosion?

If elections are held without a neutral mechanism—without some form of technocratic oversight or broad political consensus—they may become the fuse rather than the solution. The Islamists don’t want fair elections. They want a crisis. A flawed poll would give them exactly that: chaos to weaponize, martyrdom to exploit, and the streets as their stage.

Meanwhile, the military straddles both sides—talking stability while holding the threat of control over everyone. They may prefer a quiet transition. But if pushed, history shows they won’t hesitate to let the streets burn just enough to justify another “reluctant intervention.”

What’s Next?

Bangladesh stands on a knife’s edge. The interim government must act fast to build legitimacy—through transparency, inclusive dialogue, and credible electoral planning. The international community, especially those behind the UN corridor, must understand the local optics and recalibrate their involvement.

But the wild card remains the Islamist bloc. If they sense the moment is ripe, they will not wait. The Arakan issue, the student uprising template, and a visibly divided state apparatus give them the perfect storm to stage a comeback.

Bangladesh has seen revolutions, coups, and uprisings before. But this time, the mask is thinner. The banners are already waving. The question is whether anyone is prepared to stop what’s coming.